Born during some of Boston’s painful years

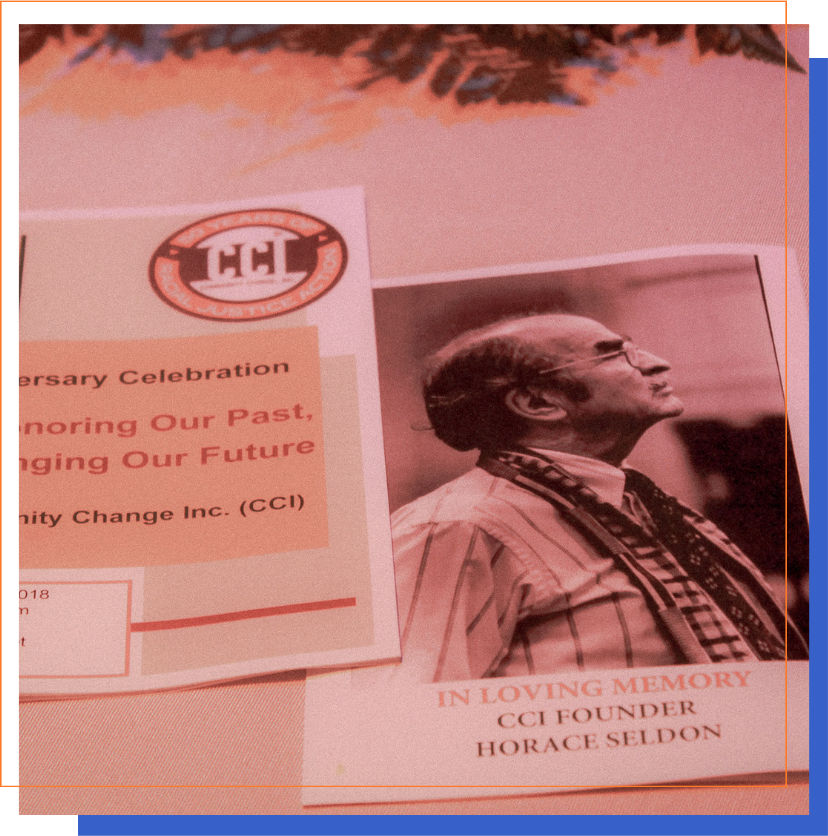

Horace Seldon founded Community Change, Inc. after the release of the 1968 Kerner Commission Report, which, for the first time, officially classified racial unrest as a “white problem.” But Boston needed CCI regardless of the national issues.

Seldon already was involved in local activism before 1968, but his work at Community Change began amid some of the ugliest racism in Boston’s history. A year prior to CCI’s founding, black mothers in Roxbury staged a sit-in at a welfare office to protest their unfair treatment that sparked riots in the neighborhood and years of racial tension. And those brave women opened the door for Seldon and CCI to join what would become the fight for desegregation in Boston Public Schools.

School segregation already was illegal in Boston, but integration was another story. The Metropolitan Council for Educational Opportunity, or METCO, was founded in 1966 as a way for suburban schools to voluntarily desegregate via a busing program, and much of CCI’s early work was focused on helping those schools prepare to cater to the needs of black students. Community Change was based out of Reading, Mass., at the time, which gave the organization easy access to many of the participating schools, as a majority of them were located north and west of Boston.

CCI held workshops “with an emphasis on ways in which administrators and teachers could more sensitively serve the urban black students who often felt and/or experienced racism in the suburban systems,” Seldon wrote (https://www.horaceseldon.com/bostons-struggle-equal-schools/). As a member of METCO’s board of directors, Seldon also contributed to many of the pamphlets and materials the organization provided to black parents to help them navigate totally new school systems with unfamiliar courses and graduation requirements. Community Change also had a couple of important members in Ruth Batson and Jean McGuire. Batson was the NAACP’s first female New England Regional Conference president from 1957 to 1960 and went on to help launch METCO as their executive director from 1966 to 1969. McGuire became METCO’s fourth ED in 1973 and focused on fighting for more black and better trained teachers in Boston’s black communities.

“The desegregational struggle became one in which Community Change became involved with many other local non-profit organizations, meeting regularly with city-wide coalitions which monitored the efforts which culminated in the 1974 court desegregation decision,” Seldon wrote. “As one of the smaller organizations in the coalitions we could not claim a major impact, but for me it was an important ‘school’ for observing and learning about institutional racism.”

Of course, anyone who knows anything about Boston’s modern history could probably figure out CCI’s beginnings weren’t easy. METCO was supposed to be a “peaceful” solution to Boston’s extreme segregation problem, but as time went on, it was anything but. That 1974 court desegregation decision Seldon mentioned led to busing riots, with white people in the city, particularly in South Boston, violently opposing the quest for equal schools. It wasn’t limited to the city, though, as CCI had plenty of work to do dealing with unrest in the suburbs, too.

Just as we’ve seen in the 2010’s, fighting for civil rights brings out the worst in those who are against any form of equality. So once desegregation finally was being enforced, racists showed their true colors, and black students were forced to deal with those effects, including an increase in Ku Klux Klan recruiting (https://repository.library.northeastern.edu/files/neu:cj82n2696) in the suburbs.

The effort wasn’t hopeless, though, and those students found allies who were influenced by work like Seldon’s and countless others involved in the fight. At Concord-Carlisle High School, for example, a group of white students organized a lunch in Dorchester with the Boston neighborhood’s black METCO students in 1978. And although there was, and still is, plenty of work to do from there, Seldon was heartened by efforts like those.

“I don’t see many white people who have any depth of concern,” Seldon told former Boston Globe reporter Gayle Pollard in 1978. “When I do, I rejoice.”